Our current exhibition, Towering Dreams: Extraordinary Architectural Drawings, includes designs and depictions of architectural wonders from around the globe. Drawings of Egyptian pyramids, Greek and Indian temples and Chinese pagodas sit alongside the images of the 18th- and 19th- century buildings which they inspired. These drawings were made or collected by Sir John Soane to help him, and his students, better understand the history of architecture and its relationship to the present day and to inspire future creations.

Some of the buildings we see in these drawings no longer exist and other designs were never even built to begin with. However, it is still possible to see quite a few of these buildings in real life. Their survival is testament their historical significance and enduring aesthetic appeal. Comparing the drawings in the exhibition with their real-life counterparts can reveal much about the draughtsman’s architectural interests and knowledge, how a building’s design might have changed over time and whether the draughtsman was drawing from life, memory or other images he had seen. They reveal what captivated artists and architects at this time and the histories that excited them.

In the UK

Soane office draughtsman, Interior perspective looking west inside Westminster Abbey, Royal Academy lecture drawing, c.1806-19, SM 76/8/5, ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

Westminster Abbey is a prime example of Gothic church architecture in Britain with which Soane had a somewhat love/hate relationship. Whilst he felt that the ‘grotesque ornaments spoil’ these churches, he appreciated their grandeur and impact. Soane favoured the use of mysterious light in his drawings to help create a sense of atmosphere within a building: in this case, a feeling of wonder and spiritual reverie.

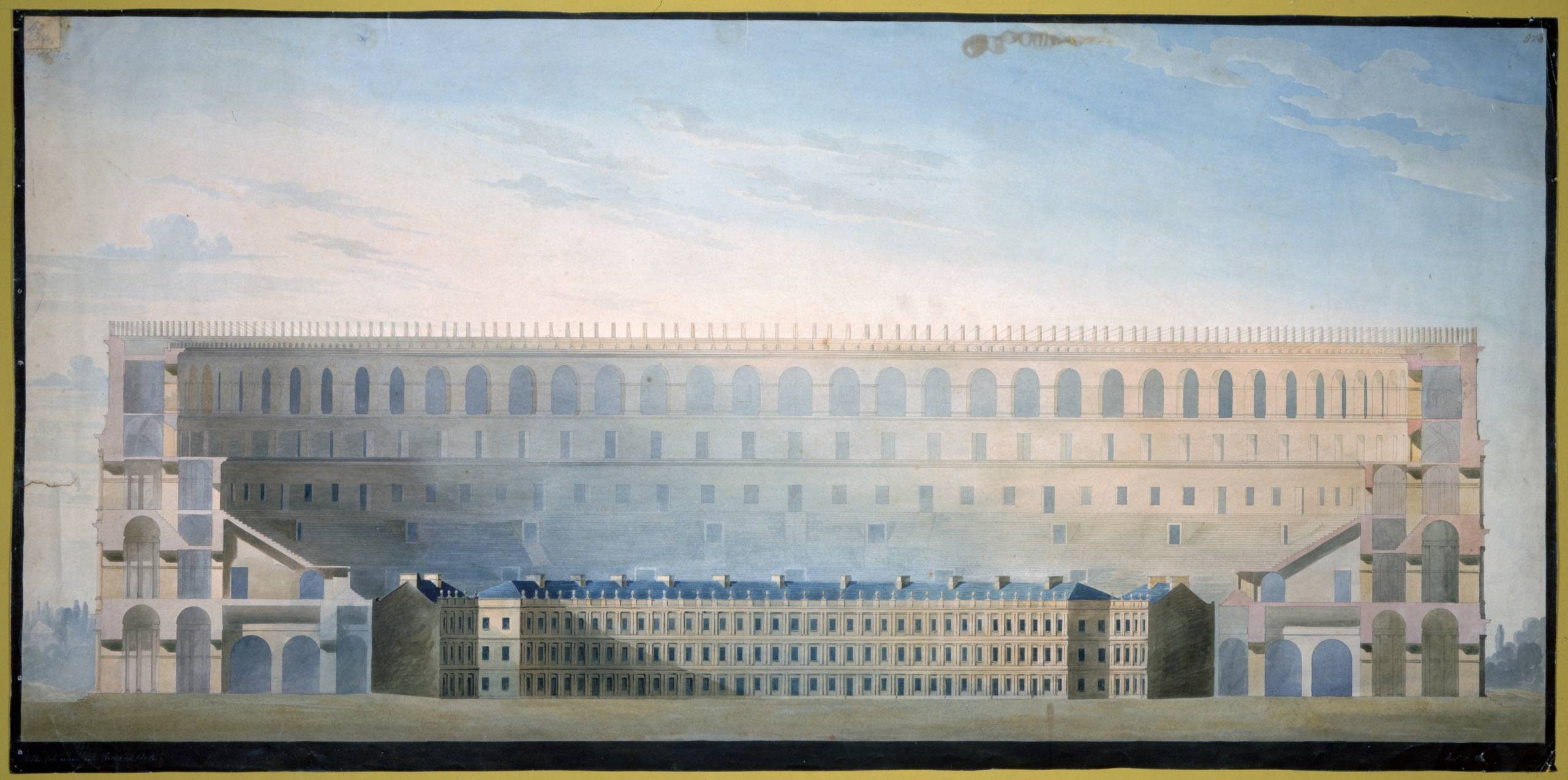

George Bailey, Comparative section of the Colosseum, Rome, and elevation of the Circus, Bath, Royal Academy lecture drawing, c.1806-19, SM 23/2/1, ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

George Bailey’s comparative drawing for Soane makes a rather comical juxtaposition – the Colosseum of ancient Rome, a symbol of gladiatorial violence, with the Circus in Bath, a symbol of polite and fashionable 18thcentury society. Here the mighty Colosseum dwarfs and overpowers its later cousin designed by the architect John Wood the Elder. Soane did not hold back when he said that: ‘The Circus at Bath … may please us by its prettiness and a sort of novelty, as a rattle pleases a child, but the area is so small, and the height of each of the orders diminutive, that the general appearance of the entire building is mean, gloomy, and confined.’ (Royal Academy Lecture 10)

Joseph Michael Gandy, Cut-away perspective showing Soane’s Church of Holy Trinity, Marylebone, c.1806-19, SM 15/4/6, ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

Gandy imbues this drawing, a cut-away perspective of Soane’s design for the Church of Holy Trinity, Marylebone in London, with an imaginative quality that underlines the architectural, rather than spiritual, ideas that it represents. Gandy imagines the building almost as a ruin, setting it among classical fragments and depicting two architectural students measuring and mapping the Church as one might record an ancient temple on the Grand Tour. The setting reminds us of Soane’s belief that great new buildings might be constructed out of the legacy of the ancient Greeks and Romans.

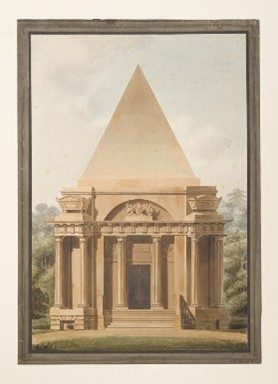

Soane office draughtsman, Elevation of the mausoleum at Cobham Hall, Keny, Royal Academy lecture drawing, 1811, SM 18/6/1, ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

The 3rd Earl of Darnley instructed in his will that his mausoleum should be in the form of ‘a prominent pyramid’. He had travelled on the Grand Tour between 1739 and 1740 and was probably inspired by the mausoleum of Caius Cestius.

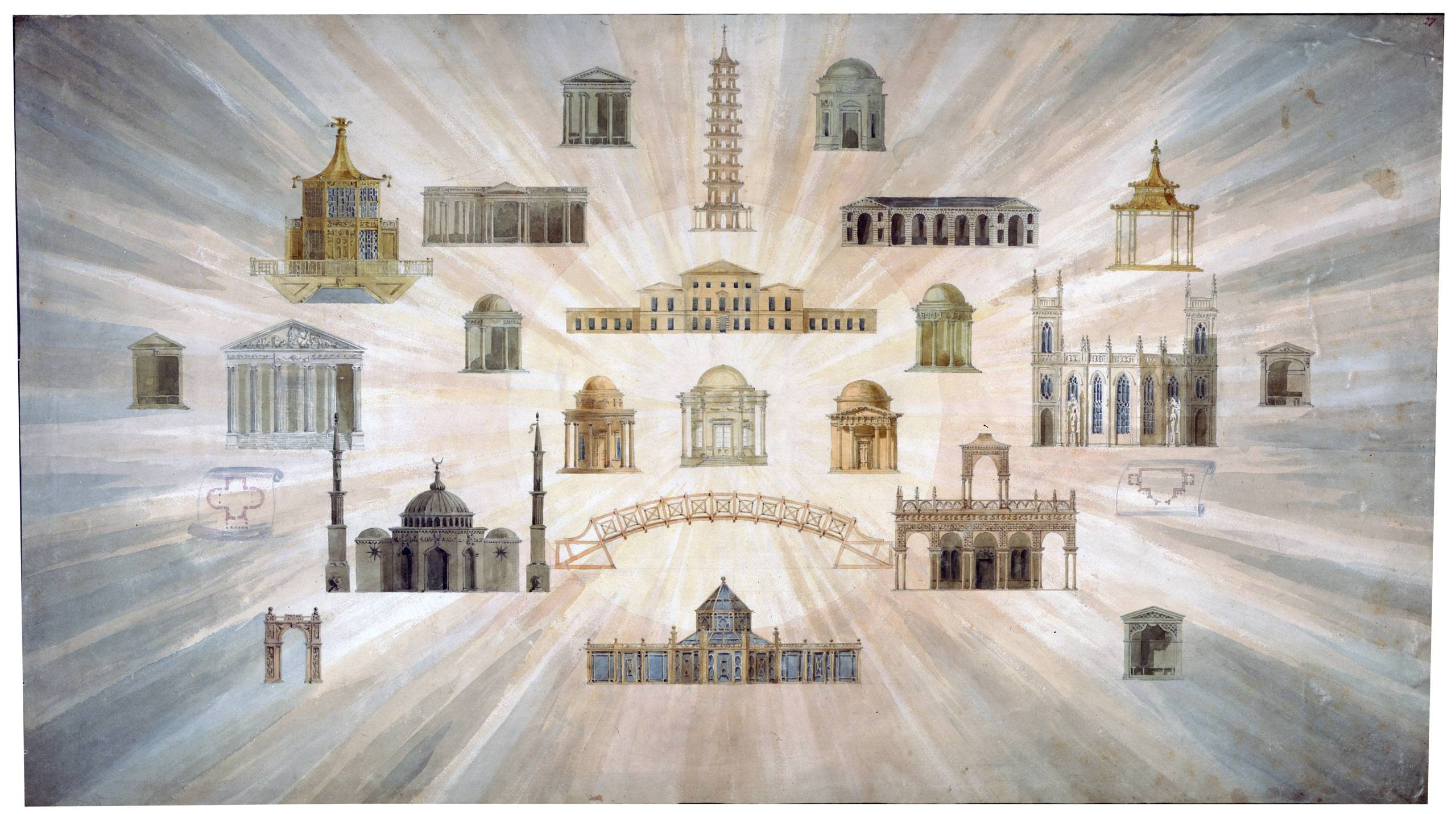

Soane office draughtsman, Montage of various buildings by Sir William Chambers at Kew Gardens, Royal Academy lecture drawing, c.1806-19, SM 17/5/6, ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

Almost like a theme park today, a walk through the grounds of Kew Gardens from the middle of the 18th century onwards allowed one seemingly to travel through different lands. Designed by Sir William Chambers, different examples of buildings from around the world were constructed across the gardens. This included a mosque, a Gothic cathedral, a Chinese pagoda, the House of Confucius, an Alhambra (modelled after the palace in Granada, Spain), a Chinese style aviary, and several Greek temples. As well as being a form of entertainment, displays such as these confirmed the prevailing belief in global British supremacy and mirrored the desire to collect and categorise animals, plants and people as part of Britain’s imperial project. Only the Chinese Pagoda remains standing today.

Further Afield

Soane office draughtsman, View of the Basilica of Maxentius, Rome, Royal Academy lecture drawing, c.1806-19, SM 20/8/10, ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

The Basilica of Maxentius was considered a marvel of Roman engineering. It was made from a combination of brick and concrete, with three colossal, unsupported arches and a vast, coffered, barrel-vaulted ceiling. Started under the Emperor Maxentius and completed under the Emperor Constantine in 312-313 CE, it was the largest structure remaining in the Roman Forum by the time of the Grand Tour. It was an important building for many architects from the Renaissance onwards and had influenced other famous buildings including St Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

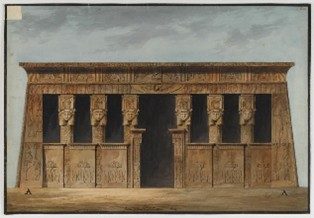

Soane office draughtsman, Elevation of the portico of the Temple at Dendera, after Denon, Royal Academy lecture drawing, c.1806-19, SM 27/3/4, ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

The 18th century witnessed a craze for Egyptian design. This ‘Eygptomania’ reached its peak in the early 19th century because of Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt and Syria, which had increased public awareness of ancient Egyptian buildings through drawings, paintings and engravings. Looted objects also made their way to Britain after various victories over the French in Egypt during this period. This draughtsman did not see this temple firsthand, instead, he was inspired by the illustrations of Baron Dominique-Vivant Denon, Napoleon’s cultural agent in Egypt and the first director of the Louvre Museum, Paris. The temple at Dendera was dedicated to Hathor, the goddess of music, joy, dance and motherhood.

Soane office draughtsman, Perspective of a cave temple at Elephanta, India, Royal Academy lecture drawing, c.1806-19, SM 24/8/1, ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

The cave temples of Elephanta, located on an island near modern-day Mumbai, were constructed in the mid-5th to 6th centuries CE. They are representative of artistic innovations in the period and their lay-out is reflective of Hindu beliefs.

The cave contains at least ten distinct representations of the Hindu god Shiva. India was increasingly accessible to British visitors due to the activities of the East India Company, a British trading body which had colonised large parts of India by this time.

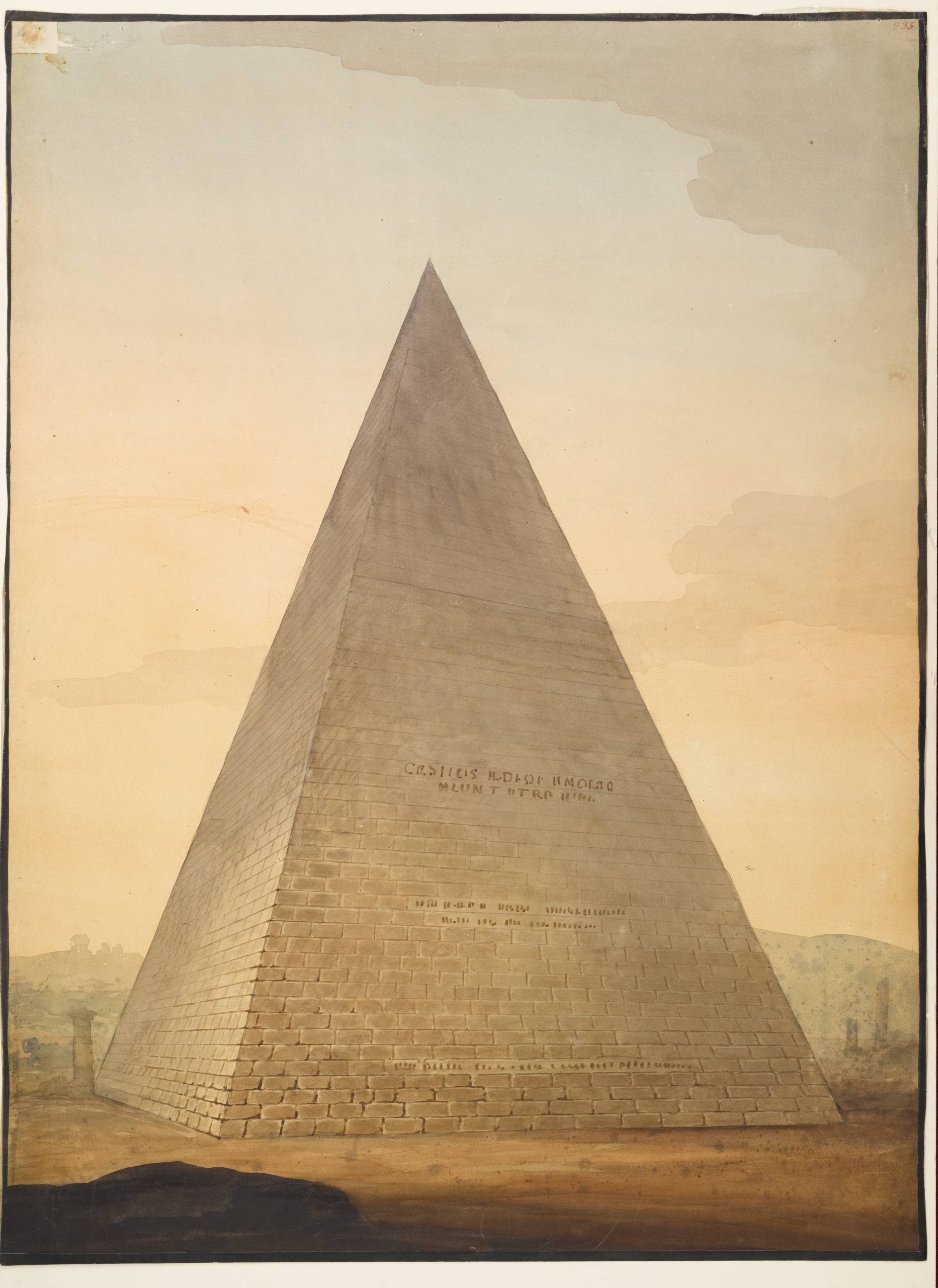

Soane office draughtsman, Perspective of the pyramid of Caius Cestius, Rome, Royal Academy lecture drawing, c.1806-19, SM 20/4/6, ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

The legend goes that Caius Cestius, a Roman magistrate, had his tomb built in the shape of a pyramid, not only due to fashion, but to prevent his wife from dancing on his grave. The pyramid is over 36 metres high and can still be seen today. It was built between 18 and 12CE but was later incorporated into the city walls under the Emperor Aurelian (c.214-275 CE). Soane’s draughtsman does not include the wall, instead situating the monument in open space with a classical background, perhaps to better appreciate its form.

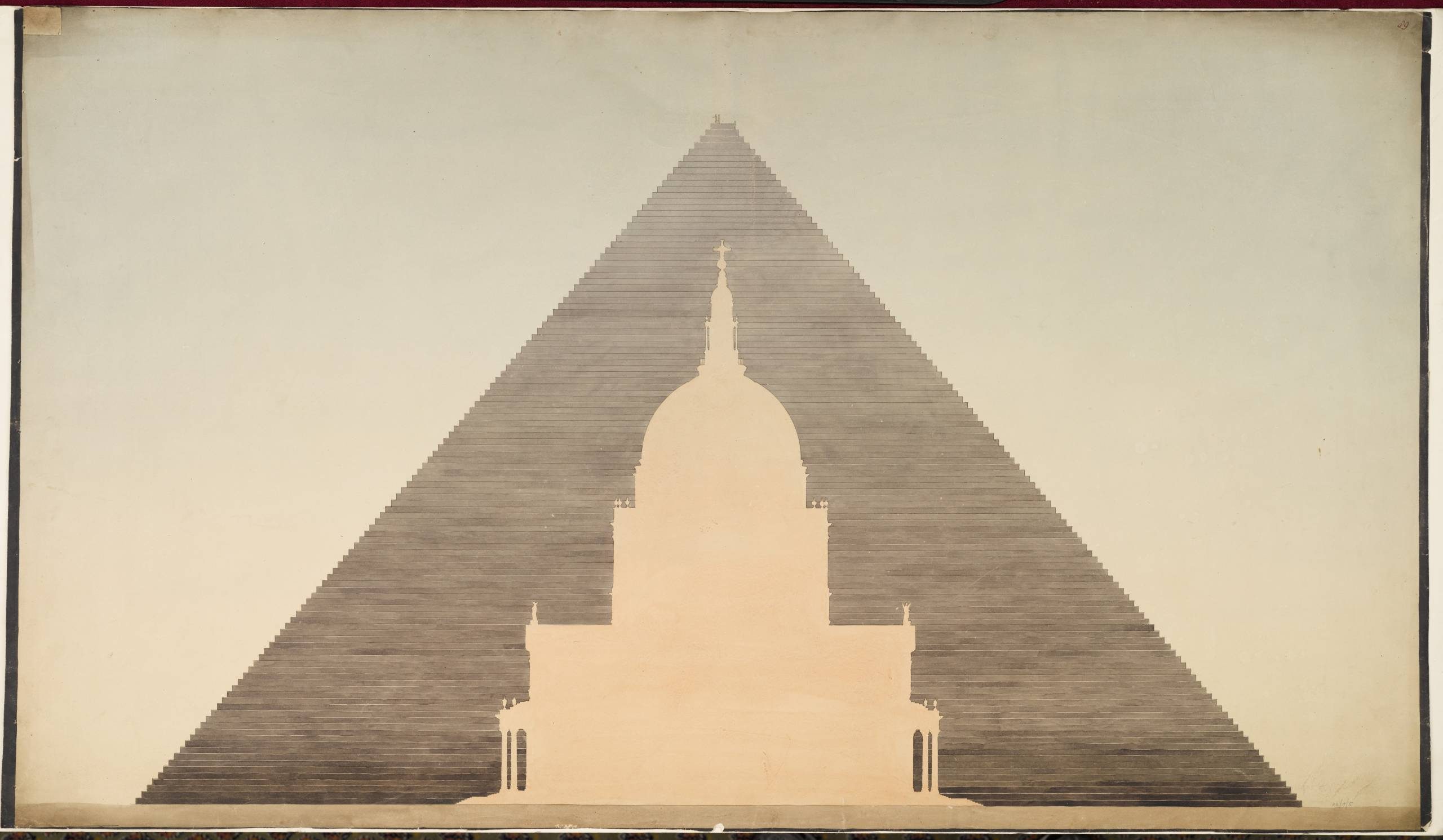

Soane office draughtsman, Superimposed outlines of the Great Pyramid at Giza and St Paul’s Cathedral, Royal Academy lecture drawing, c.1806-19, SM 22/9/5, ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

What might you learn if one of London’s most celebrated buildings, Sir Christopher Wren’s St Paul’s Cathedral, was placed side by side with one of the seven wonders of the world, the Great Pyramid at Giza? The two buildings could not be more different, with over 4000 years separating their construction. This drawing perfectly encapsulates the imaginative and fantastical theorising that architects undertook during this period.

The Towering Dreams: Extraordinary Architectural Drawings exhibition is proudly supported by SE-Solicitors.

![]()